Musings of a NARA Researcher: Hurdles to Scanning

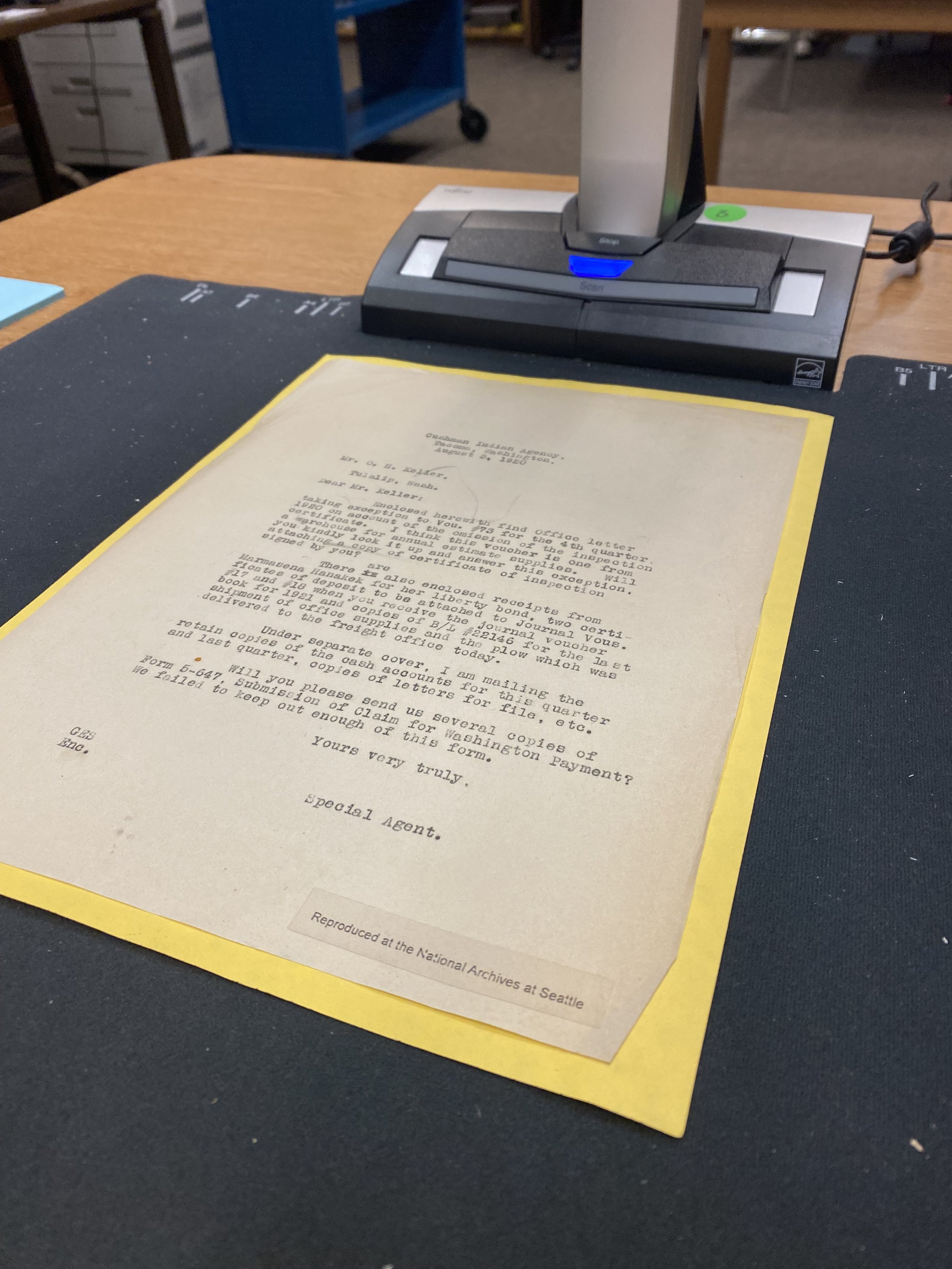

Our first day of scanning at NARA Seattle using the tools of the trade - a Fujitsu Snap Scan and a lap top computer.

As I shared in my previous post, my colleague Angela (Angie) Wade and I were contracted by the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition (NABS) to digitize boarding school records housed at the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) in Seattle. This six-week project was funded through a grant that covered two full-time contractors working on-site, five days a week, from 9:00 AM to 4:00 PM—the full operating hours of the NARA Seattle Reading Room.

NABS set an initial project goal of producing a combined total of 40,000 scans. On paper, this seemed ambitious but doable. But as anyone who’s worked in digitization knows, what looks reasonable on paper doesn’t always translate to reality—especially when you're navigating the real-life complexities of scanning archival records.

Having worked on numerous digitization projects, I can confidently say that scanning speed depends on multiple factors:

The type of scanner being used

The condition, format, and size of the materials

And, just as importantly, the well-being and focus of the person doing the scanning

At first glance, 20,000 scans per person over six weeks might seem achievable. But once you consider the actual setup and workflow, that number quickly begins to feel like a stretch.

The Scanner Situation

At home, I use an Epson V600 flatbed scanner—widely considered an industry standard for high-resolution archival work. Although these scanners were technically allowed at NARA, they aren’t exactly portable or user-friendly for fieldwork. They're bulky, take time to set up, and each high-res scan can take 30+ seconds—too slow when you're racing the clock.

NABS instead provided us with Fujitsu Snap Scan (now known as a Recoh Snap Scan) overhead scanners—lightweight, backpack-portable, and easy to set up. They’re great for travel and relatively efficient, scanning standard documents at 600 dpi in about 10–15 seconds. While 600 dpi is fine for access copies and digital sharing, it doesn’t always meet long-term preservation standards—but that’s a conversation for another post.

At first, things didn’t go smoothly. My Snap Scan constantly encountered errors once the scan count reached 100 pages in a session. It turned out this was caused by a recent software update Fujitsu had rolled out just before I received the equipment from NABS. I ended up losing almost an entire day of scanning to troubleshoot the issue with Fujitsu’s support team over the phone. Fortunately, once resolved, the scanner performed significantly better, with only the occasional hiccup.

Scan Totals: From Frustration to Progress

Due to the scanner issues, my first three weeks were painfully slow. I averaged around 230 scans per day, which was far below where I needed to be to meet the overall target. But after the software problem was resolved, I steadily built momentum—eventually reaching 600 to 800 scans per day.

Still, the early delays had already affected my overall output, making it clear that the original 40,000-scan goal hadn’t fully accounted for the real-world variables that come with field digitization projects.

The Challenge of Fragile Materials

The second major factor (after scanner performance, which I covered last time) was the nature of the materials themselves. Much of what we were tasked with digitizing dated to the early 1900s and was printed on onion skin paper—a notoriously delicate material comparable in texture and strength to the thin tissue you find in fast food or stadium restrooms. Not the soft, quilted kind.

After decades of wear, these documents had become brittle and clingy, often stuck together due to static. Separating and flattening them carefully for scanning took significant time and focus. To complicate matters further, transparency issues meant we had to place a solid-colored backing behind each sheet just to make the printed text readable in the scan.

And that wasn’t all.

NARA requires each item scanned to be marked with a small identifier tag, which must be placed and removed between scans. Additionally, documents were often bound together with a variety of metal fasteners—staples, tacks, and even pins—that had to be carefully removed. In some cases, we needed help from NARA staff, who used tiny archival spatulas to safely extract them without damaging the records.

Just a sample of the variety of fasteners you can find on archival documents.

The Final Hurdle: Caring for the Scanning Technician

One of the most overlooked—but absolutely critical—factors in any digitization project is the well-being of the person doing the scanning.

Digitization work requires long hours of repetitive motion—sitting or standing while closely monitoring a screen, editing image files, and organizing metadata. Over time, this leads to physical strain: aching backs, stiff necks, tired eyes. Add to that the environmental conditions of working in a federal archive, and the toll can increase quickly.

As an archive, NARA must maintain strict environmental controls—cool, dry air to preserve fragile records. While essential for the materials, these conditions can take a toll on the body. No food or drink is allowed in the Reading Room, so if you’re not careful, you can easily become dehydrated or lose track of your hunger cues during long scanning sessions.

That’s why it’s so important for visiting researchers and scanning technicians to build in regular breaks, stay hydrated outside the Reading Room, and bring a nourishing lunch. Your body will thank you, and so will your productivity.

But the physical challenges are only part of the equation.

Digitizing boarding school records—particularly student case files—comes with a heavy emotional weight. These documents often reveal stories of abuse, neglect, and cultural trauma. Reading through them day after day can stir grief, anger, and deep emotional fatigue, especially for those of us who carry intergenerational connections to these histories.

So while output metrics matter, so does the care and mental health of the people behind the work. Emotional labor is real. And in projects like this one, it’s unavoidable.

Recognizing this, Angie and I were intentional about checking in with each other, taking time to step away when needed, and honoring the emotional impact of what we were encountering. It’s essential—because cultural work is people work. And caring for our histories means caring for ourselves in the process.

Some challenging content you can come across in archives is not just the information that is documented but also how it is documented. You can often find antiquated or offensive language such as the phrase used in this correspondance.

The Reality of Remote Digitization Work

So what’s the big takeaway from all this?

Even the best-laid plans can fall apart—and that’s okay. Scanning projects, especially remote ones, are full of unknowns. You won’t always know the condition or complexity of the materials until you’re physically with them. Your equipment may need adjusting. You might encounter tech issues, policy constraints, or—let’s not forget—you’re working away from home, often out of a suitcase. That adds stress.

Take care of your team. Your people are your greatest asset. Make sure they feel supported—logistically, emotionally, and professionally. A successful project isn’t just about output—it’s also about sustainability and care.

In the end, despite all the hurdles, Angie and I scanned over 30,000 pages, or roughly 15,000 each—a solid accomplishment considering the circumstances. Thankfully, NABS was incredibly supportive. Rather than viewing the missed target as a failure, they used our experience as a learning opportunity to inform future project planning and build more flexible, realistic expectations for research teams moving forward.

Our work in Seattle showed that digitization is never just about numbers. It’s about navigating the complexities of history, technology, and human capacity—with care, adaptability, and purpose.

Angie and I with the amazing archival team from NARA Seattle: Patty, Michelle, Britta and Crystal (sadly, Valerie was absent).